Expertise

Intact soil despite heavy machinery

Michael Kuhwald | 17.12.2025

Soil compaction is almost invisible—but its consequences for soil health and yields are all the more serious. The Thünen Institute of Agricultural Engineering is researching where the greatest risks lie and how farmers can counteract them.

Almost every piece of agricultural land is driven over several times a year, whether for sowing, fertilizing, or harvesting. On wet soil, the pressure of the machines is clearly visible in the form of tire tracks. The effects inside the soil, on the other hand, are almost invisible, but all the more significant: air-filled pores are compressed and the soil becomes compacted. As a result, water flows off the surface instead of seeping into the soil. This increases the risk of water erosion – at the same time, yields and yield security decline.

The compaction of the deeper subsoil is particularly problematic because the soil there can only be loosened mechanically with great effort and often with limited success. Natural regeneration hardly takes place and takes decades. Over the years, the stresses in the subsoil can accumulate and thus limit soil functionality in the long term.

Agricultural machinery puts strain on the soil

Wheel load has continued to increase over recent decades. At the same time, there have been significant advances in tire technology, meaning that farmers can now drive over their fields with lower tire pressures. This increases the contact area of the wheels and distributes the load more evenly. The load then does not penetrate as far into the subsoil.

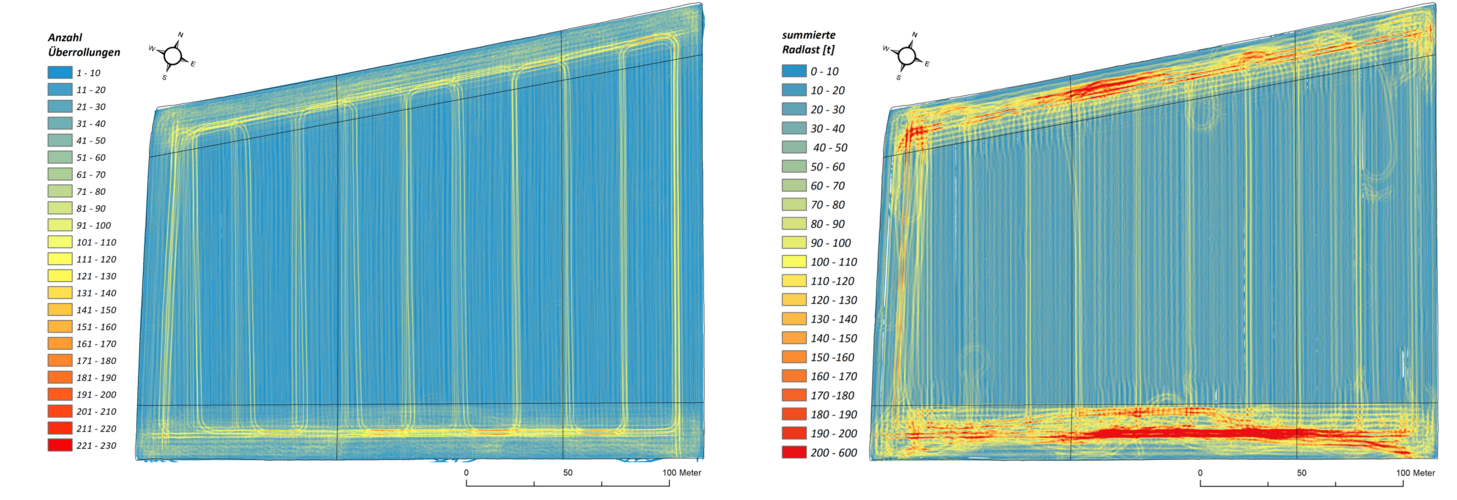

The frequency of driving also has an impact on soil compaction. As a general rule, the more often a soil is driven on, the greater the loss of soil functions. The first time a soil is driven on usually causes the most significant change.

The load can be measured using pressure-settlement measurement systems developed by researchers at the Thünen Institute of Agricultural Engineering. The sensors are buried in the field and record the pressure exerted on the soil when driven over, as well as the settlement of the soil, i.e., how strongly the pores are compressed.

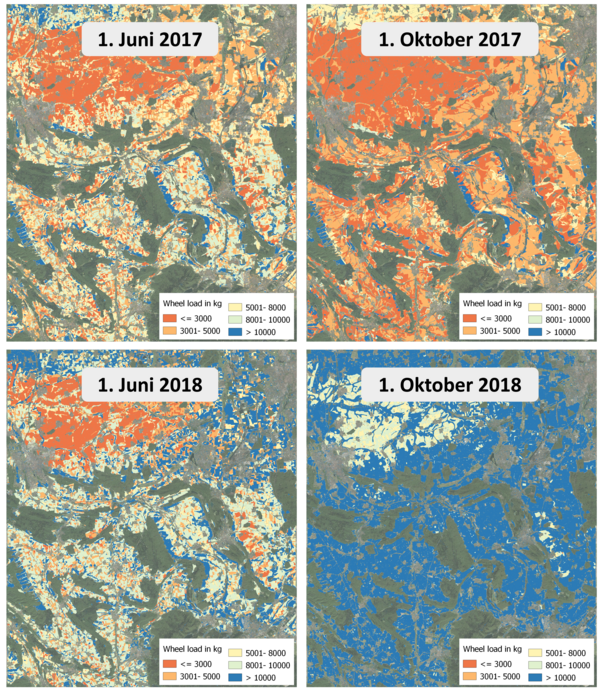

The load-bearing capacity of soils depends on weather conditions

Depending on the location and weather conditions, soils react differently to the stress caused by agricultural machinery. The decisive factor here is how wet or dry the soil is at the time of driving over it: the lower the soil moisture, the more stable and resilient the soil is. This means that in very dry years, even the heaviest machines can drive over it without causing any damage. For example, despite high wheel loads and frequent driving, the corn harvest in the extremely dry conditions of 2018 did not leave any harmful soil compaction. In the previous year, the soil was significantly wetter and less resilient.

In addition to soil moisture, humus content, soil structure, and soil type—i.e., how sandy or clayey a soil is—also determine soil stability. Well-structured and well-rooted soil can withstand higher loads. A freshly plowed field, on the other hand, has lost much of its structure. It immediately gives way under load and deep ruts form.

Using computer models, Thünen researchers are working with scientists from Kiel University to calculate how resilient Germany's soils are over the course of the year. To do this, they use data on soil moisture and crop rotations, for example.

Reduce load, strengthen soils

Gentle driving is achieved when the machines only exert as much pressure on the soil as its structure and condition allow. The most effective approach is to promote soil structure throughout the year and not to drive on the land in wet or damp conditions. In practice, this is often only possible to a limited extent due to time and cost pressures. If farmers have to work in the fields despite unfavorable conditions, it is advisable to drive on the fields as little as possible and with low tire pressure and low wheel load.

To help farmers choose the right measures for their land, researchers at the Thünen Institute of Agricultural Engineering and Kiel University have published profiles of the most effective approaches.

Farmers can protect their soil from harmful compaction by:

- Growing cover crops. Cover crops keep the soil covered between main crops. Their roots loosen the soil and stabilize its structure. This makes the soil less susceptible to compaction, erosion, and silting.

- Working the soil gently. Gentle cultivation loosens only the topsoil and preserves its structure. Plant residues remain largely on the surface as mulch, which maintains load-bearing capacity and reduces soil compaction.

- Make machine use more flexible. If agricultural machinery shared by several farms is only scheduled for 80 percent of the time instead of 100 percent, farmers can respond more flexibly to changes in weather. For example, they can postpone driving on wet days to another day.

- Store slurry tanks at the edge of the field. If the slurry is piped from the edge of the field to the vehicle, the heavy tanker does not have to drive across the field. This protects the soil from compaction and at the same time creates more scope for field work despite wet conditions.

- Use modern tire pressure adjustment systems. A tire pressure adjustment system allows the pressure to be adjusted depending on the application: in the field, it is lowered to increase the contact area, reduce ground pressure, and minimize compaction; on the road, it can be increased again.

- Use dual tires and wide tires. Wide and dual tires increase the contact area of the wheels, thereby reducing pressure on the ground.

All information on these and other strategies for preventing soil compaction can be found on the website of the German research initiative Soil as a Sustainable Resource for the Bioeconomy (BonaRes).

Further information

- In the SOILAssist project, researchers are working with farmers to develop strategies for soil-conserving land management. The Thünen Institute is coordinating the joint project.

- The targeted selection and adjustment of chassis can help to drive on arable land in a way that protects the soil. Thünen scientists are working with researchers from all over Germany and Switzerland on the “Soil-friendly driving” project to find out how this can be achieved.

- The learning and information media on soil compaction in arable farming, which were developed in the SoilAssist research project, can be downloaded free of charge from the BonaRes research initiative website.

- The Thünen explains video “The subsoil – Deeply rooted in dry times” shows how important it is to consider the subsoil when farming.

Contact

- Phone

- +49 531 2570 2313 /+49 531 596 4164

- michael.kuhwald@thuenen.de