Fact check

Has European fisheries management systematically failed?

Christopher Zimmermann, Gerd Kraus, Alexander Kempf | 05.08.2025

An opinion piece in Science magazine claims that the poor state of Baltic Sea fish stocks is due to a systematic failure of fisheries management, including the scientific advisory system involving national fisheries research institutions and the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES). What are we to make of this criticism?

Instead of continuing to rely on established systems, the group of scientists led by Kiel-based lead author Rainer Froese suggests in the Science article that a group of researchers independent of politics should take over key aspects of fisheries management. This would ensure that ecosystem-based upper limits for catch quantities are set that politicians can no longer tamper with. Is this a viable solution?

For their opinion piece “Systemic failure of European fisheries management,” the team of authors led by Kiel scientist Rainer Froese selected several examples of fish stock management in the EU. The most prominent example is the western Baltic Sea, especially herring and cod. The researchers attempt to show that, year after year, ICES has submitted excessively high catch recommendations to the European Commission. They argue that this is due to a flaw in the calculation system, which is ultimately one of the causes of the failure of European fisheries management. Furthermore, they claim that ICES catch recommendations are not independent of political influence, as high catch recommendations are in the interest of politicians.

Repeated attacks on the ICES

ICES is an independent, intergovernmental body based on an international convention that also includes non-EU members such as Canada, the US, Iceland, and Norway. The fisheries management of these countries is considered globally advanced and sustainable. Their governments also seek advice from ICES on fisheries issues, at least in part.

To ensure the independence and reliability of its recommendations, ICES follows ten carefully selected principles in its work. The rules require, for example, the use of the best available data and findings, as well as comprehensive and unambiguous recommendations. As is customary in science, the results of the scientific working groups' work are independently reviewed (“peer reviewed”). At each stage of the development of a recommendation, it is ensured that scientists whose nations have no specific fishing interests in the regions covered are also represented in the drafting process. In the Baltic Sea group, for example, researchers from the US, Iceland, and Ireland regularly participate. Despite considerable uncertainties in its predictions, ICES has been providing globally recognized scientific advice as a basis for fisheries management for 120 years. Froese, on the other hand, repeatedly discredits the work of ICES without providing any reliable evidence.

Is the Baltic Sea a good example?

After a long period of overfishing, other man-made stressors are now the main factors affecting the Baltic Sea. For many years, the Helsinki Commission, which is responsible for monitoring the marine environment, has identified increasing eutrophication, or overfertilization, as by far the most important factor influencing the state of the ecosystem. This is followed by climate change, pollution, and overfishing. Some of these factors reinforce each other. In particular, warming and excessive nutrient concentrations are leading to an expansion of oxygen-depleted or even oxygen-free areas in the deeper regions of the Baltic Sea, and now also in the western Baltic Sea. This development has a significant impact on the distribution, food supply, and habitat of fish. In addition, important predator species such as gray seals and cormorants, as well as parasites, are on the rise. The problem is that these factors are currently changing faster than ever before. The models used to calculate the state of the environment can no longer predict these changes. As a result, stock models tend to make overly optimistic predictions of sustainable catch levels rather than overly pessimistic ones. This is because science can only draw conclusions about the future based on observations from the past. Anything else is fortune telling. Years later, it is possible to criticize the assumptions about future developments as deliberately overly optimistic in retrospect—and rightly so, from this perspective they were overly optimistic, but not deliberately so.

ICES responded to this in 2020. Since then, measures to correct systematic deviations have been part of stock assessments and forecasts. Assumptions and uncertainties are communicated transparently. As a result, the EU Council of Ministers, taking these uncertainties into account, has set lower catch quotas than recommended by scientists. This was the case, for example, with cod in the western Baltic Sea in the years 2020 to 2023. After that, targeted fishing was completely closed.

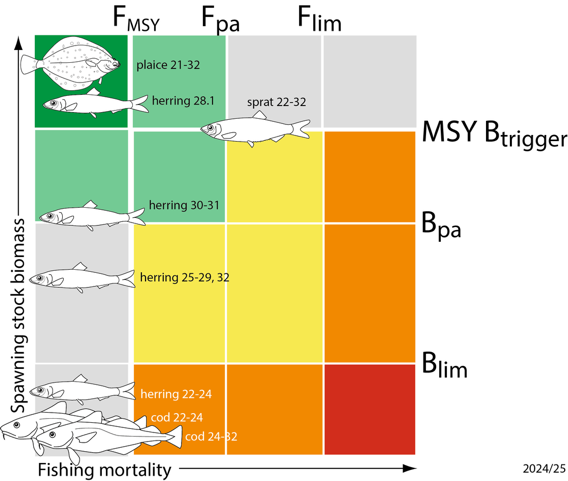

Despite all the factors that are difficult to predict and sometimes interact chaotically, it has been possible to reduce fishing pressure over the past ten years to such an extent that the impact of fishing on cod and herring stock developments in the western Baltic Sea is no longer significant (see figure).

The systematic overestimation of stock sizes in ICES calculations claimed by the Kiel authors also fails to stand up to scrutiny elsewhere. In 2025, the predictions for 63 stocks assessed by ICES were analyzed using analytical stock calculations. The deviation between the predicted spawning biomass and that observed in the following year averaged three percent.

Are historical values a useful benchmark?

In the Science article, the authors compare current catches from the western Baltic Sea with what they consider to be the maximum sustainable yield (MSY). They choose the period from 2003 to 2022 for their analysis and identify the largest landing of 97,548 tons in 2004. However, numerous stocks were overfished during this period. The catch levels were therefore already unsustainable at that time and led to a decline in stocks. It is also certain that such high catch levels will no longer be achievable in the foreseeable future due to changed environmental conditions and the resulting reduction in productivity. The team of authors is therefore, against their better judgment, making precisely the assumptions that they accuse ICES of being too optimistic about. In other publications, they themselves point out that ecosystems are not static and that reference values must therefore be carefully adjusted to changed parameters. This applies to the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) as well as target values for biomass (Bmsy) or limits for fishing pressure (Fmsy).

Has EU fisheries management failed?

The Science article claims that European fisheries management has failed. To understand this, we need to look at the tasks of fisheries management: The most important task is to reduce fishing pressure (F) to a sustainable level, as this is the only way to increase biomass and achieve maximum sustainable yield (MSY). This is the declared goal of sustainable management in the EU and many other regions of the world. This goal has not yet been achieved for all EU stocks. However, the trend is clearly positive. The number of fish stocks in EU waters of the North Atlantic that are overfished (F > FMSY) has fallen from just under 75 percent in 2004 to almost 20 percent in 2023. The fact that the goal of fishing all stocks according to the principle of maximum sustainable yield was not achieved by 2020 as planned is open to criticism. However, to speak of systematic failure ignores the enormous progress that has been made.

Should scientists set the quotas?

In their article, the Geomar researchers present a relatively simple solution: in the EU, ecosystem-based limits for maximum catch quantities should be calculated by an independent scientific institution. These limits should then not be exceeded by politicians. What this demand means in concrete terms, what criteria must be met in order to be considered independent, who appoints this body and its members, remains open. Above all, however, the difference to the current approach is not clear, because such an independent scientific institution already exists: the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), which develops management recommendations each year based on the principle of consensus, sound and responsible science, and controversial discussions. The analyses and recommendations include reference points for biomass and fishing pressure, which are even binding in connection with the multiannual management plans adopted by the EU Parliament. The analyses and recommendations include reference points for biomass and fishing pressure, which are even binding in connection with multiannual management plans adopted by the EU Parliament. Nevertheless, the Council of Ministers has the option of deviating from the scientific recommendation under certain circumstances. And that is a good thing, because we believe the proposal by the Kiel researchers is undemocratic: a scientific institution is not legitimized by elections. Furthermore, there are no scientific answers to many key decisions in fisheries management: do we want a sprat- or cod-dominated ecosystem in the Baltic Sea? Do we accept longer recovery periods for overfished stocks in order to enable more fishing businesses to survive, or do we want the opposite? Science that advises politicians therefore offers options, but it does not make decisions. This is the sole responsibility of democratically legitimized political institutions.

Further informatiion

Froese R, Steiner N, Papaioannou E, MacNeil L, Reusch TBH, Scotti M (2025) Systemic failure of European fisheries management. Science 22 May 2025: 826–828

Lordan et al 2025 ICES response to: Systemic failure of European fisheries management. eLetter to Science 17.07.2025:

Scotti M, Opitz S, MacNeil L, Kreutle A, Pusch C, Froese R (2022) Ecosystem-based fisheries management increases catch and carbon sequestration through recovery of exploited stocks: The western Baltic Sea case study. Front. Mar. Sci., 05 October 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.879998

Guide to ICES advisory framework and principles

Baltic Sea Ecoregion - Fisheries Overview

Scientific Technical and Economic Committee for Fischeries (STECF)