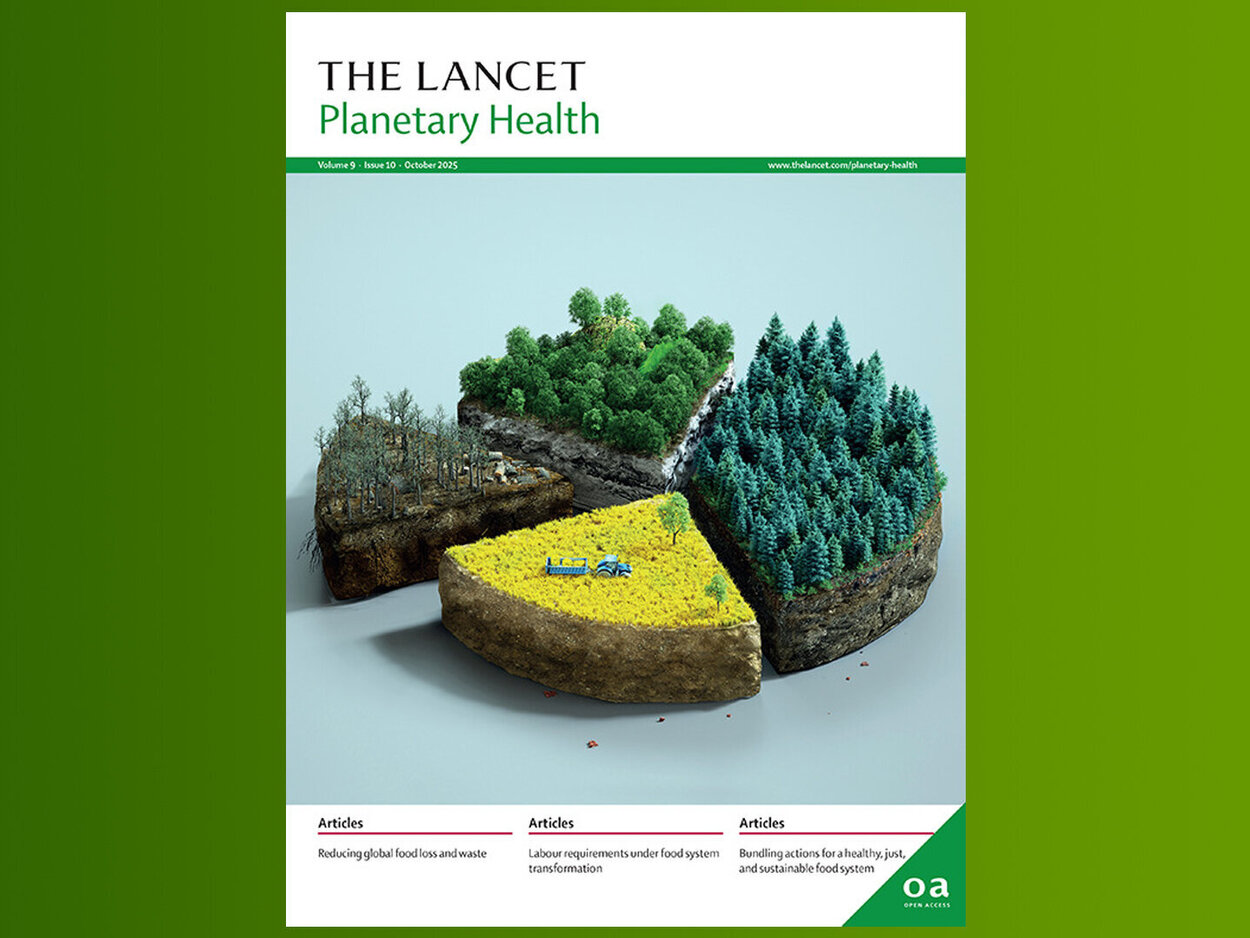

One of the authors is Dr Ferike Thom, a scientist at the Thünen Institute of Farm Economics. She works on the TRIP research project, Greenhouse Gas Reduction through Innovative Breeding Advances in Alternative Plant Protein Sources, a project funded by the German government through its Immediate Climate Protection Programme. During a research stay at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) in Seville, Thom was involved in modelling the Planetary Health Diet using the CAPRI model. "It was a unique experience for me to be able to work in such a large, international network," says Thom. "I learned a lot about how models work. I now have a better understanding of the strengths and limitations of CAPRI," says the scientist.Models are an essential part of research: researchers use them to describe how, for example, dietary habits or the climate will develop in the future. These models are based on current data and assumptions made by the scientists themselves. But who are these people who design the models? And which perspectives are missing from their models? These are the questions being asked by a group of ten young scientists in the international research network AgMIP (Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project). Together, they have just published a joint viewpoint in the renowned journal The Lancet Planetary Health. This is the first time that insights into the perspective of young researchers on a large, global modelling project have been published: the Planetary Health Diet (PHD) of the new EAT-Lancet Commission.

One of the authors is Dr Ferike Thom, a scientist at the Thünen Institute of Farm Economics. She works on the TRIP research project, Greenhouse Gas Reduction through Innovative Breeding Advances in Alternative Plant Protein Sources, a project funded by the German government through its Immediate Climate Protection Programme. During a research stay at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) in Seville, Thom was involved in modelling the Planetary Health Diet using the CAPRI model. "It was a unique experience for me to be able to work in such a large, international network," says Thom. "I learned a lot about how models work. I now have a better understanding of the strengths and limitations of CAPRI," says the scientist.

In their contribution to The Lancet Planetary Health, the early career researchers reflect on structural inequalities in global research. One example: while the models simulate dietary changes worldwide, all participating institutions are located in the Global North. Gender differences are also apparent: there is gender parity among the junior scientists, while around 80 per cent of the senior scientists are men. The authors therefore call for a more equitable and inclusive international research culture that better combines diversity and sustainability.

In addition, they identify areas for further development of the models, such as improved representation of consumer dietary behaviour. The Viewpoint emphasises that future modelling should take into account the entire value chain, from the cultivation of raw products to processing and trade to the consumption of composite foods. Only in this way can the economic, ecological and health consequences of dietary change be truly comprehensively assessed.

"In order to develop realistic future scenarios, models need to better reflect how dietary behaviour can actually change. So, for example, we need to find out which political, social or economic incentives motivate people to eat more sustainably and healthily," explains Thom. “This offers great potential for making modelling results more meaningful and relevant for political decisions.”

Parallel to the Viewpoint, the same Lancet Planetary Health special issue also features an article on the global impact of the Planetary Health Diet, based on the AgMIP modelling results of the Planetary Health Diet, in which Ferike Thom was also involved.