Interview

The soil is thirsty

Nadine Kraft | 10.06.2025

The Thünen Institute not only monitors the development of forests and oceans over long periods of time, but also of agricultural and forest soils. The third National Soil Inventory (BZE) is currently underway on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Regional Identity (BMLEH). At the halfway point, and following a very dry spring, we spoke to the people responsible for the BZE Agriculture, Dr. Christopher Poeplau of the Thünen Institute of Climate-Smart Agriculture, and the BZE Forest, Dr. Nicole Wellbrock of the Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems, about the condition of our soils.

Ms Wellbrock, Mr Poeplau: How are our soils doing?

Nicole Wellbrock: The biggest problem for all soils is drought. In agriculture, you can irrigate. This is expensive and comes at the expense of drinking water resources. That does not work in the forest. You cannot exactly water the trees for 80 years. One option would be to water new plantings in the beginning. In forests, we are mainly concerned about the deep soil water storage, which refills only slowly. As drinking water is often extracted from beneath forests, drought poses a particular challenge.

Christopher Poeplau: In addition to the drought, we have two other long-term problems on agricultural land. 50 per cent of all arable soils are heavily compacted. Even if there is enough rain, the water often cannot soak into the soil at all or it does not reach deep enough. The second problem is the loss of humus.

What about known pressures on forests, such as nitrogen pollution?

Wellbrock: Nitrogen deposition from the air into the forest have been a problem for a long time. On the one hand, they cause over-fertilisation and on the other they lead to soil acidification. Heavy metal contamination now only occurs in isolated areas, such as in mining regions. This is just as much a success of air pollution control as the significant reduction in sulphur emissions, which caused the so-called forest dieback in the 1980s.

What helps against compacted soils?

Wellbrock: Soil compaction is less of a problem in the forest. Usually, vehicles only drive on the skid trails for harvesting. On the damaged areas, heavy machinery was sometimes driven outside the skid trails to quickly remove the affected trees. As a result, the soil there is now compacted.

Poeplau: Conservation tillage is becoming increasingly important. There is less ploughing to avoid damaging the soil structure and to help retain moisture. The focus is shifting to the subsoil. Nutrients and water are available there. But the plants often reach it. Catch crops are a kind of universal aid. They protect against erosion, can create channels in the subsoil through which other plants then take root better. And they also protect against the loss of humus.

Why is the loss of humus particularly noticeable this time?

Poeplau: The focus of the BZE is on climate reporting. Alongside forests, humus is the most important carbon store on land. Until now, it was assumed that agriculturally utilised mineral soils were neither a source nor a sink for carbon. The forest with its soil was a sink. The plan was to increase humus on agricultural land and thus store more carbon, creating at least a small sink. However, the forest itself has now become a source, and in the BZE we are also observing a loss of humus.

Wellbrock: The forest soil has been a carbon sink for a long time. However, due to the widespread dieback of trees, the leaf fall, and the roots of dead trees, the carbon input into the soil will initially increase significantly. Subsequently, the humus supply will decrease until new trees have grown back. The BZE III 2026 will show what impact this will have.

Do you have an explanation for the loss of humus?

Poeplau: We have yet to find a really clear explanation as to why humus levels in the soil are declining now of all times. We suspect this is also due to historical factors, that is, the way the land has been used and covered over the past decades, or even centuries.

What do you recommend?

Poeplau: As a farmer, it is important to keep an eye on the humus content of your own land. Not only for climate protection, but also for soil fertility and climate adaptation. We still believe that maintaining a permanent ground cover, with plenty of below-ground biomass, is very effective. Scholars have been arguing about what constitutes a good humus content for a very long time. The fact is that soils relatively rich in humus are harder to improve than those with low humus levels. The probability of losing more humus is also higher for these soils. We have determined what is currently typical for the site by analysing the status quo of the 3,000 soils in the National Soil Inventory. We have prepared the results in a way that farmers can use them as well.

And in the forest?

Wellbrock: There is no soil management in forests like there is in the fields. Humus can be preserved and increased in the soil through silviculture and the conservation of vital forests. Therefore, the conversion to climate-stable forests is very important for the soil as well, so that it not only remains a carbon store, but can also fulfil ecosystem functions such as providing clean drinking water. We can already see that the conversion of coniferous forests to more deciduous forests is having an impact on the soil. In the organic layer of coniferous forests, the humus reservoir is lower than in mineral soils. Forest liming can also help to promote vitality in heavily anthropogenically acidified sites.

And the peatlands? They are currently being praised as climate saviours...

Poeplau: This is correct from a climate perspective. Peatland used for agricultural purposes will continue to be a source of carbon. This could be prevented by re-wetting large areas of moorland. Wetland farming, known as paludiculture in agriculture, is also an option. There is only one per cent of natural moorland left in Germany.

Wellbrock: Re-wetted forest peatland also have great potential for climate protection. Around three per cent of the forest area is peatland, most of which is drained. However, alder is the only tree species, that can survive in fully drained conditions. Conversely, this means that if they are re-wetted, the tree species that previously stood there will die off.

Background BZE and BZE-Forest:

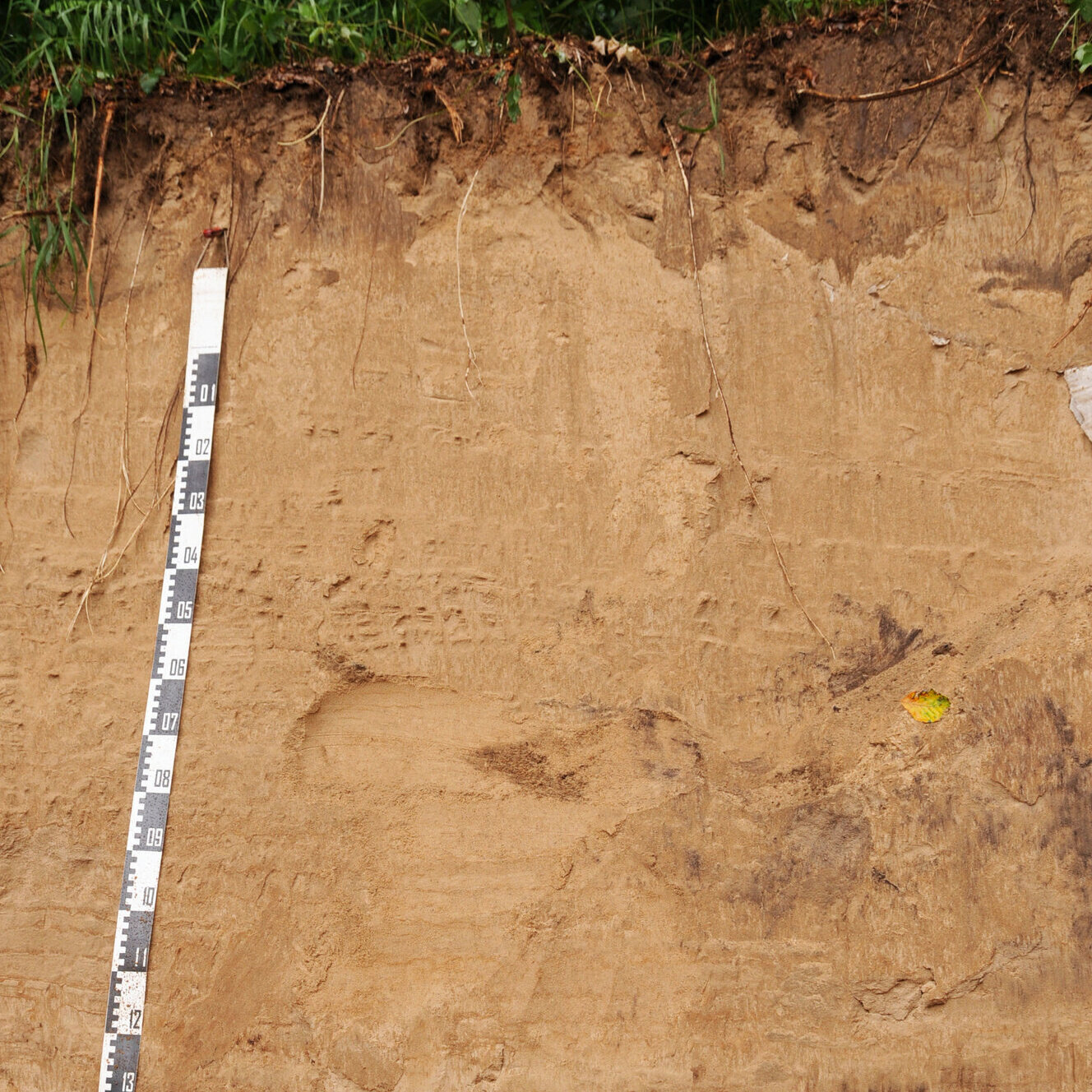

As a counterpart to the National Forest Soil Inventory (BZE-Wald), which exists since the 1980s, the Agricultural Soil Inventory (BZE-LW) was carried out for the first time between 2011 and 2018. The repeat of the inventory has been running since 2022. More than 3,000 arable, grassland, and special crop sites are sampled down to a depth of one metre in a systematic grid. The aim is to obtain a representative picture of soil carbon stocks in agricultural soils in Germany. This data and sample set is a central basis for national emissions reporting for greenhouse gases. At the same time, it forms an important basis for soil research at the Thünen Institute.

The BZE and BZE-Forest data are collected at the Thünen Institutes of Climate-Smart Agriculture and Forest Ecosystems on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. The working groups are headed by Dr. Christopher Poeplau and Dr. Nicole Wellbrock. For the first time, data on biodiversity and biological activity in the soil will also be collected as part of the BZE-Forest. By integrating all biological and non-biological data, the researchers hope to gain a better understanding of the contribution of forests and forest soils to biogeochemical cycles. This in turn will enable them to derive recommendations for forest conversion in times of global climate change. At the same time, knowledge gaps on the state of biodiversity in Germany's forest soils are to be closed.

Our interview partners

- Phone

- +49 3334 3820 304

- nicole.wellbrock@thuenen.de

Head of Soil protection and forest health, Contact person National Forest Soil Survey and Crown Condition Survey

- Phone

- +49 531 596 2679

- christopher.poeplau@thuenen.de