Populism—understood as an ideology that divides society into two antagonistic groups (e.g., the elite and the people)—is at its core always based on a conspiracy narrative. This is empirically supported by the fact that citizens who are inclined to believe in conspiracy theories are more likely to support populist parties.

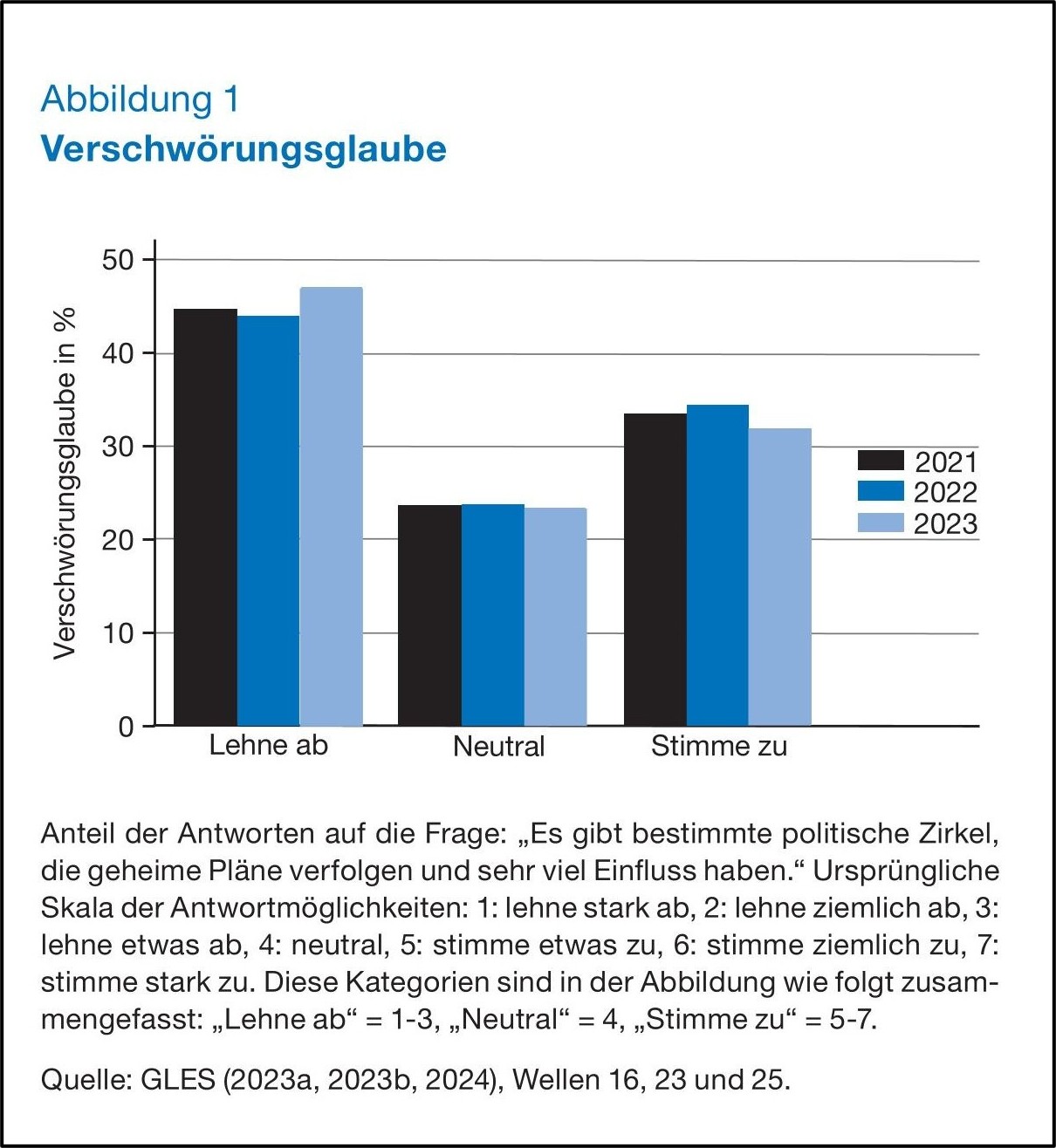

In their contribution, however, Lena Gerling and Thomas Apolte (University of Münster) show that —unlike, for example, support for the right-wing populist party AfD— support for conspiracy narratives has not increased over time. How can this empirical puzzle be explained? Drawing on economic theories of voting behavior, the authors argue that one explanation may lie in the decline of party identification. Non-populist politicians are less able than in the past to effectively bind to their respective parties those segments of the population that adhere to conspiracy narratives.

The authors suggest that the electoral successes achieved so far by populist parties—reinforced by social media and by drivers of social contagion—may prove to be remarkably stable. They therefore recommend strengthening democratic institutions in such a way that authoritarian politicians cannot inflict damage on the democratic order. In this context, effective barriers to accessing executive power play a crucial role.

Article (in German): „Verschwörungsmythen und populistische Wahlerfolge – wie die Politik reagieren kann“

Contact: Dr. Lena Gerling

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/media/_processed_/6/1/csm_AdobeStock_543466681_9df3d40718.jpeg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/media/_processed_/6/1/csm_AdobeStock_543466681_6eab1c26f9.jpeg)