Sea blog

On a research cruise with the L'Atalante

Thousands of barrels of nuclear waste lie on the Atlantic seabed — but where exactly? An international expedition involving the Thünen Institute of Fisheries Ecology is now trying to find out.

Duration: 16 June to 11 July 2025

Cruise area: Northeast Atlantic

Purpose: Mapping nuclear waste drums in the Iberian deep sea

Cruise leader: Javier Escartin (IFREMER)

Blog author: Pedro Nogueira

The day began early in the morning with the loading of personal luggage and climbing the 10 metre high gangway of the L'Atalante (IFREMER), a ship built in 1989 with a length of 84.6 metres and a width of 15.9 metres. So far, I've only taken part in research cruises on the Walther Herwig III (BLE), so I'm really looking forward to getting to know the many possibilities of this French ship and finding out how work and life on board differ from a German research vessel.

This voyage, led by Javier Escartin, is the first of two voyages as part of the NODSUMM project. Its aim is to map nuclear waste storage sites and take samples of marine life, sediments and water samples in the Iberian deep sea. Barrels containing a total of 42 PBq of low-level radioactive material were dumped in this region between 1967 and 1983.

My job on board is to take fish samples for radioactive measurements. I also support the radiation protection team on board, which is responsible for the initial measurements of the samples and ensures that no people are contaminated with radioactive substances that have been lying on the seabed for 40 years.

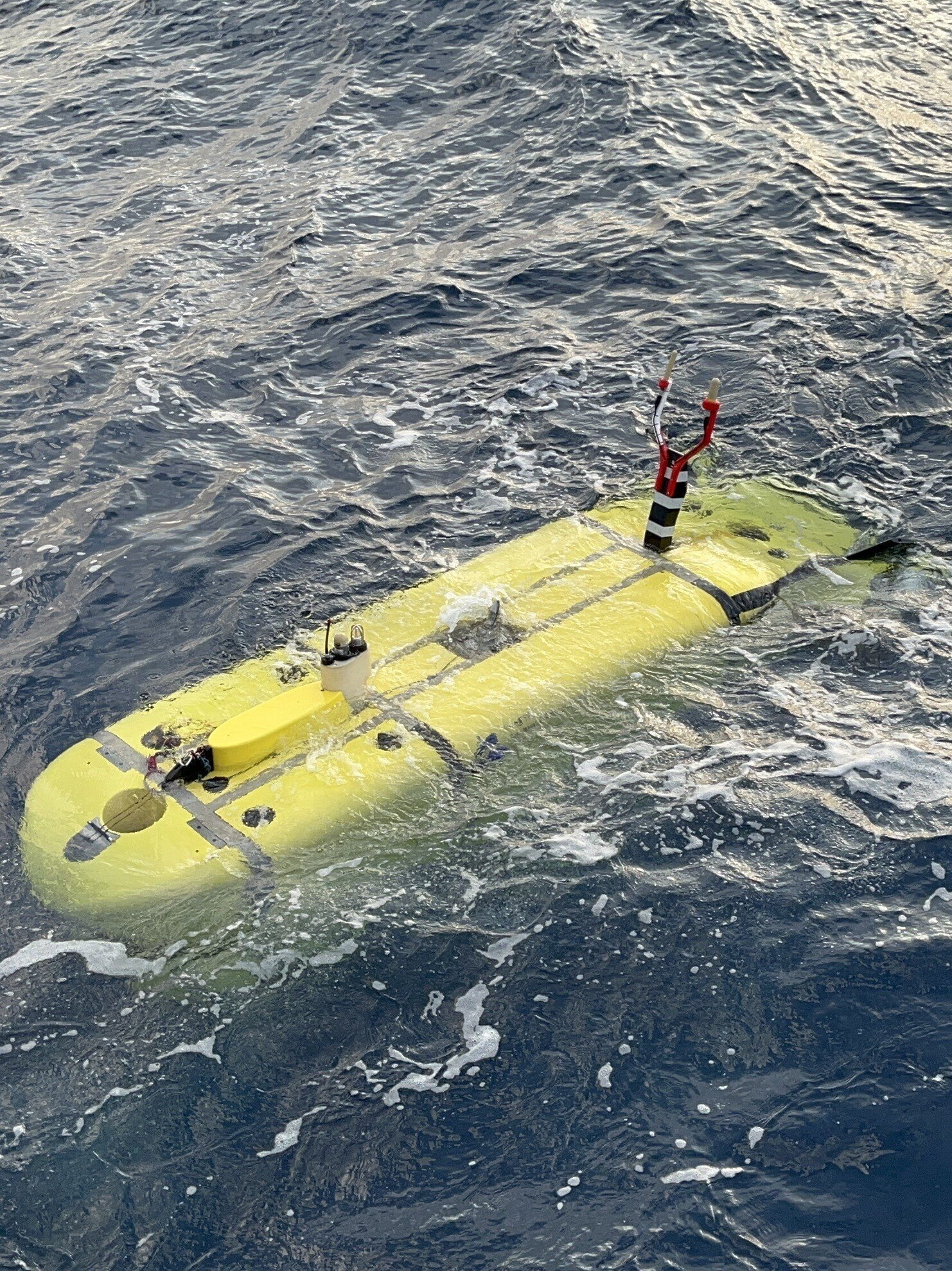

By the end of the morning, the autonomous underwater vehicle "Ulyx" had been successfully tested. In the afternoon, we started unpacking the scientific material and exploring our new home for the next four weeks.

The first days of the cruise were dedicated to setting up the scientific equipment and familiarising the crew with its use for water (CTD rosette sampler), sediments (multicore drill) and fish (traps). As usual, this time was also used for the safety briefing, trying on the rescue suits and later for the evacuation exercise.

The first tests were carried out in moonlight to check the functionality of the CTD rosette and the multicorer. On the way to the Iberian Deep Sea, we made a short stop at a previously determined test site. The depth in this area is around 2100 metres, so the waiting time for the CTD sampler is 2.5 hours and two hours for the multicorer. After the long wait, the radiation protection team was deployed. To ensure safety on board, the first samples were measured using a small radiation detector for beta and alpha radiation, followed by a 30-minute gamma measurement using a germanium detector.

Two traps were set up in the control area today. They were attached with chains to a 500 kg cement block at the bottom and to six floats, several localization devices and a flag at the top. In total, this system is 40 m long and weighs 465 kg. An acoustic release system was mounted between the weight and the trap. As the name suggests, this system is activated by an acoustic signal that releases the upper part (trap and float) from the weight.

Before anchoring the two traps, several pieces of mackerel were packed in bags and placed in the traps. We also rubbed the entrance to the trap with fish in the hope that the fish will find the entrance more easily. In addition, a small trap for amphipods was set up in the fish trap, a small tube with a cone through which the amphipods (amphipods) can enter but not exit.

We are excited to see what strange sea creatures we will catch.

The first two deployments of the fish trap brought in only small catches - just two amphipods. These were specimens of Eurythenes gryllus, a large deep-sea scavenger that resembles a shrimp. Unlike most amphipods, which are usually tiny, E. gryllus can grow to an impressive 14 centimeters in length. It inhabits the ocean’s deepest zones, from about 500 meters down to more than 7,000 meters.

As a key part of the deep-sea food web, Eurythenes gryllus feeds on organic matter that sinks to the seafloor, such as dead fish or marine mammals. Thanks to its highly developed sense of smell, it can detect food from a great distance in total darkness. When a large carcass reaches the seabed, groups of these amphipods often appear quickly to feed.

Much about their reproductive biology remains a mystery. However, like many deep-sea species, they likely reproduce slowly. Females carry eggs in a brood pouch, and the young hatch as miniature versions of the adults. Due to the cold, nutrient-poor environment they inhabit, these amphipods grow slowly and may live for over a decade.

On the third and fourth trials, we had better luck: each trap contained two specimens of Coryphaenoides armatus, also known as the abyssal grenadier. This deep-sea fish is a common resident of the ocean’s abyss, often found at depths beyond 5,000 meters. It has a long, tapering body, a large head, and prominent eyes - well-adapted for life in the cold and darkness of the deep.

Like the amphipods, C. armatus plays an important role in recycling organic material that sinks from the surface. It feeds on carrion as well as live prey like small crustaceans and worms. Its keen sense of smell helps it locate food in the absence of light.

Reproductive behavior in this species is also not fully understood. It is thought to spawn infrequently, producing relatively few large eggs. The young likely spend a long period drifting in the deep sea before settling. Slow growth and low reproductive rates are common among deep-sea creatures, and C. armatus may live for several decades - perhaps as long as 50 years.

Today we carried out a special deployment at a depth of 4,700 meters. Using heavy cement anchor, originally designed for mooring fish cages, we transported and released several ceramic ammonites created by the artist Marina Zindy into the abyss.

These ceramic pieces were carefully fixed to the fish cages anchors and lowered to the seafloor, where they will remain for years to come. The idea behind this act is both scientific and symbolic. According to Marina Zindy, the placement of the ammonites on the deep-sea floor is a symbolic and poetic artistic gesture – a way to connect human creativity with one of the most remote and extreme environments on Earth.

However, Zindy is also clear-eyed about the message: “It cannot heal what humans are doing to the ocean.” Her work acknowledges the deep impact of human activity on the marine environment, while at the same time offering a quiet, reflective moment at the interface of science, art, and nature.

Over time, we hope to revisit the site to observe whether marine life interacts with these sculptural forms. Will they become colonized by organisms? Will they change shape or color under deep-sea conditions?

This unusual collaboration between science and art reminds us that the ocean is not only a field for measurement and data, but also a place of memory, transformation, and human emotion.

Since the beginning of our expedition, we’ve been working closely with the AUV Ulyx, one of the most advanced deep-sea exploration vehicles in the world. Ulyx belongs to the French oceanographic fleet and is operated by Ifremer. It can dive to depths of up to 6,000 meters and is equipped with high-resolution sonar, allowing for detailed mapping of the seafloor. On this cruise, Ulyx is being used to help locate radioactive waste barrels that were dumped in the North Atlantic by the Nuclear Energy Agency between 1967 and 1983. Its autonomous capabilities, combined with precise navigation and imaging systems, make it an essential tool for investigating these historic deep-sea dumping sites.

Using the high-resolution sonar images generated by the Ulyx it was possible to identify until now the localization of more than 1,300 barrels.

Addendum of 30 June 2025: more than 1,800 barrels have now been found.

Today, in addition to my sampling for radioactivity measurements, I took water samples for my new colleague Kenneth Arinaitwe. He is interested in measuring PFAS (per- and polyfluorinated alkyl compounds) in fish, sediments and seawater at different depths.

PFAS do not occur naturally, but are produced industrially. PFAS include several thousand different substances that are used, for example, in the manufacture of breathable, water-repellent clothing, but also in many other areas. They accumulate in the environment because they degrade very slowly and are therefore also referred to as “eternal chemicals”. Some of these substances are also suspected of being carcinogenic.

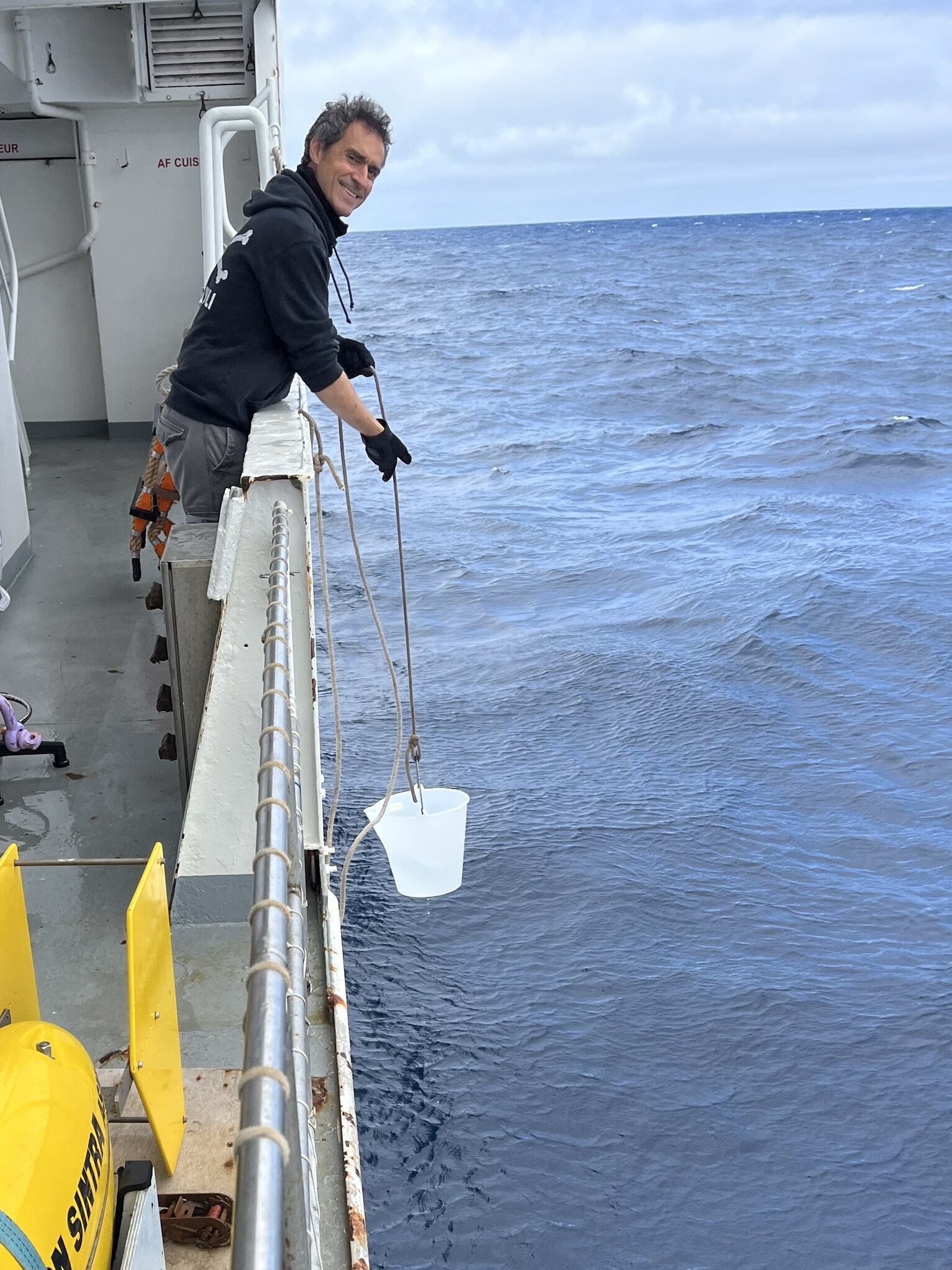

I used the CTD rosette to take water samples at four different depths: at 4703 meters (above the sea floor), at 763 meters (from the Mediterranean current), at 400 meters and at 50 meters (with maximum chlorophyll content). I took a final sample at the surface using a rope and a bucket.

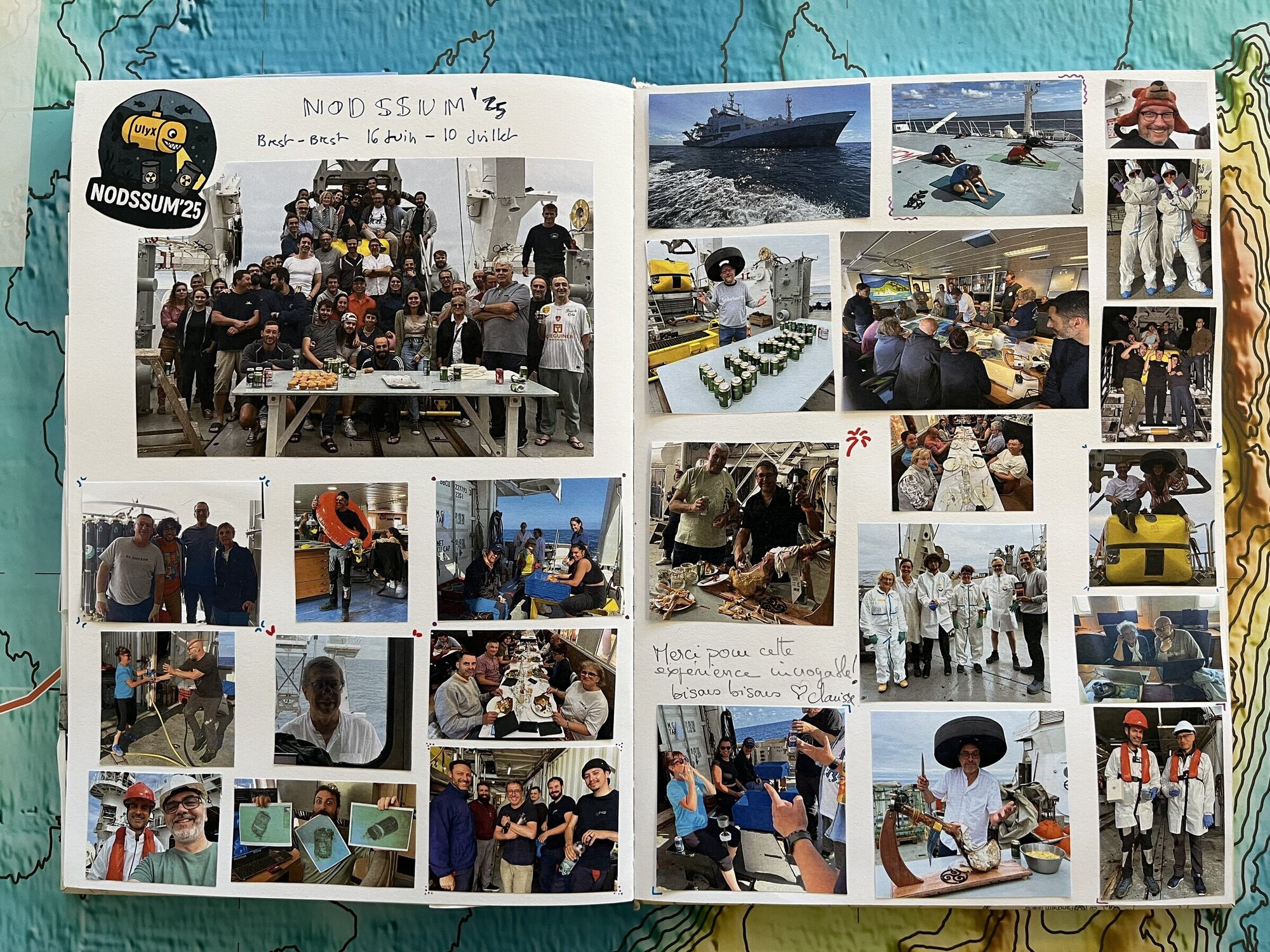

Today was our last day of operations. However, our work is not entirely finished yet. Between packing up our scientific equipment and cleaning the laboratories, we still found time to celebrate with a farewell party together with the entire crew. And last but not least, we added our entry to the ship’s guest book — a small tradition to mark the end of an unforgettable cruise.

Over the past four weeks, we collected 5,000 liters of water samples, 345 sediment cores, 19 biological samples, and numerous additional smaller samples.

Using the Ulyx sonar system, we mapped approximately 3,350 barrels across 163 km² of sonar-imaged seafloor. So far, over 5,000 photos have been taken during optical surveys, covering around 38,000 m². Roughly 50 barrels were documented photographically – image analysis is currently ongoing.

A preliminary review of the barrel images suggests varying states of preservation: some barrels appear intact, others deformed or ruptured. Many show corroded surfaces and are colonized by sessile organisms like sea anemones. In some cases, leakage of unknown substances was observed, likely bitumen.

Onboard radiation safety instruments detected values close to natural environmental background levels. However, precise laboratory analyses of sediments, water, and fish samples will require several months.

During the expedition, beside my scientific work, I gave 12 interviews to German newspapers, radio, and TV stations. It was an intense but rewarding cruise: I learned new methods, worked with a great team, and even made a few new friends. If I had to summarize the past month in just two words I would say: “Great Success!”