Project

Migration behaviour of tope (HTTP)

Helgoland Tope Tagging Project

It is the largest shark found permanently in German waters and is globally classified as "critically endangered": the tope. Tagging experiments with satellite transmitters in the North Sea will provide information on the migratory behaviour of the animals and thus allow a reliable assessment of the distribution of the sharks and their population development.

Background and Objective

Tope (Galeorhinus galeus) is globally listed as 'Critically Endangered' on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and as 'Endangered' in German waters.

Adult tope undertake extensive migrations throughout their distribution range. Juveniles, on the other hand, remain closer to shore for longer periods of time, e.g. in their nursery areas.

The extent and causes of adult migrations are not fully understood: in other parts of their almost circumglobal range, the migrations of adult females are associated with reproduction - they regularly visit pupping areas where they give birth to their offspring. While migratory routes and regular migration patterns have been established for other populations, such information is still scarce for the north-east Atlantic population.

Although there is no targeted fishery for tope in European waters, they are regularly caught in a wide range of fishing gears and landed as by-catch. Technical measures to prevent unwanted by-catches of tope are not feasible given the large number of fishing gears used in fisheries. This makes it all the more important to be aware of important tope habitats, i.e. areas where the animals are found regularly and possibly for longer periods of time. These are, for example, the areas where juveniles are born (pupping areas) or where adults aggregate to feed or reproduce. In these areas, more effective spatially and/or temporally explicit measures can be taken to better protect this endangered shark species.

In order to fill in the existing knowledge gaps on distribution, migration, behaviour and general biology of tope in the northeast Atlantic, adult specimens are caught and tagged with satellite and conventional tags during their summer aggregation off Helgoland.

The objectives of the project are

- to identify seasonal migratory movements of tope in the North Sea

- to investigate the biological basis of summer aggregations of tope in the German Bight and their diurnal vertical migrations and activity cycles.

- to collect data to assess the conservation and vulnerability status of this Red List species in German waters and the North-East Atlantic.

- to collect data on the distribution of adults in order to assess the benefits of existing and planned protected areas for the conservation of (migratory) sharks.

Target Group

Science, policy (fisheries, conservation)

Approach

In summer, adult tope gather in the German Bight around Helgoland. There, we use rod and line to catch specimens feasible for tagging from a boat. After recording length, weight and sex and taking a tissue sample for genetic population analysis, a satellite tag (MiniPAT) and a classic spaghetti-tag (floy tag) are attached to and underneath the dorsal fin in a quick, minimally invasive procedure. The animal is then gently released.

After deployment, the tags internal sensors continuously record depth, temperature and ambient light for a pre-programmed period of time. Afterwards the tag detaches from the shark and surfaces. There the stored sensor data are transmitted via satellite.

The data can then be used to reconstruct the migration routes of this highly migratory species. In addition, small-scale behavioural patterns such as possible daily activity cycles and habitat preferences of the sharks can be determined. Possible regular concentrations of sharks in a certain area at a certain time may be relevant for the establishment and monitoring of marine protected areas.

Data and Methods

In this project, Pop-Up Archival Transmitting Tags or Satellite Pop-Up Tags (PAT Tags or PSAT), model MiniPAT, are used. The tags are programmed and placed in standby mode prior to field operations. Once a shark has been tagged and released, the tags activate upon contact with seawater and begin collecting data. For a pre-programmed period of 270 to 365 days, the tags record environmental parameters such as temperature, depth and light intensity every few seconds. During this period there is no 'contact' with the tagged shark, so we do not know where the shark is or what it is doing while the data is being collected. Only at the end of the measurement phase does the tag detach from the animal and rise to the surface. Once there, the stored data is transmitted via ARGOS satellites.

The data can then be used to reconstruct the sharks' movement patterns, activity cycles and migration routes from the time of deployment until the tag detaches. For example, near-surface temperature data is compared with surface temperature data from research satellites, and depth data is compared with bathymetric data from the study area. The change in light intensity at certain depths and times of day can also be used to derive information about the geographical position at a particular time.

Information about depth distribution, preferred thermal habitats, etc. can be derived by comparing the time periods the sharks spent at certain depth ranges and by analysing, for example, the temperature range in which the animals preferred to stay.

Sharks are also fitted with a 'spaghetti' tag - a type of ear tag - that will help in gathering additional biological data in case the shark is caught again after the satellite tag has detached.

Our Research Questions

- How can we characterize the (seasonal) migratory movements of tope sharks in the North Sea/Northeast Atlantic?

- Can we identify spatial and temporal patterns in migration routes and aggregation behaviour, as well as diurnal migration and activity cycles?

- Can we use data on the migratory movements and habitat use of tope to identify so-called "critical habitats"/ important areas and assess the suitability of existing and planned marine protected areas for the protection of this threatened species or identify possible conservation measures?

Preliminary Results

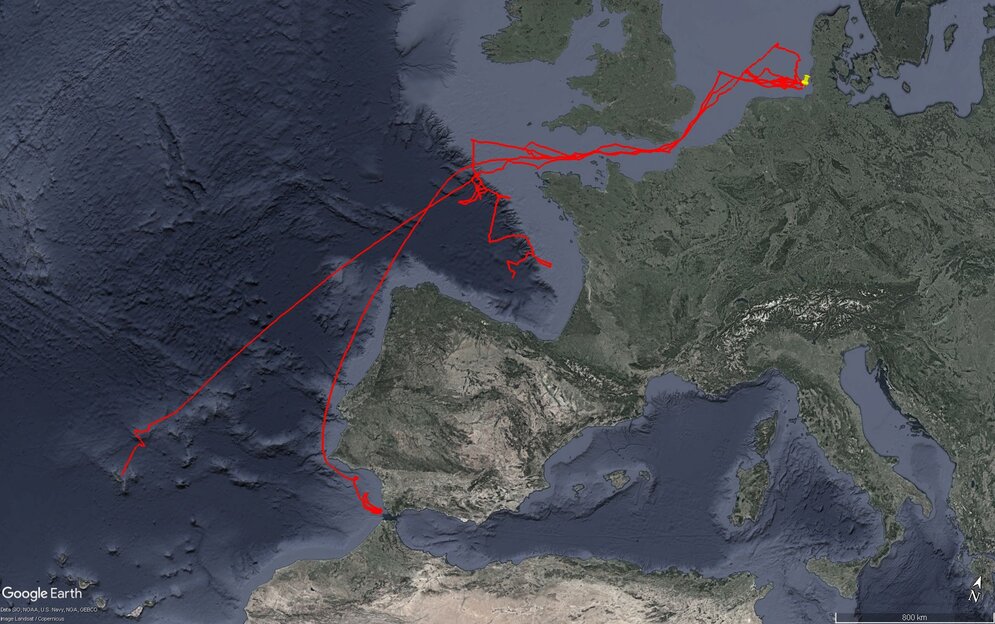

Since the start of the project, 22 tope sharks have been tagged. From the data collected so far, it has been possible to reconstruct the migration routes and some behavioural patterns of individual sharks. The majority of all tagged sharks left the Helgoland area with the autumnal cooling of the seawater and migrated westwards along the East and West Frisian Islands and then southwestwards into the English Channel. Many spent the winter months there.

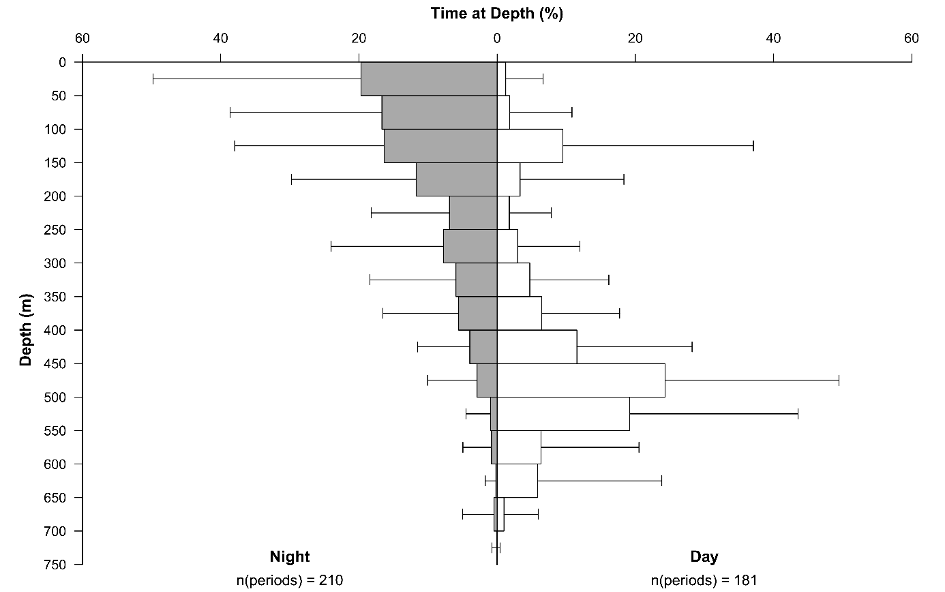

Some of the sharks migrated further into the Northeast Atlantic, leaving the shallow continental shelf in the Bay of Biscay and moving into the open ocean - in some cases obviously purposefully as far as Madeira or the Strait of Gibraltar. Not only did the animals cover distances of several thousand kilometers, but they also undertook pronounced vertical migrations into mesopelagic layers as soon as they entered oceanic habitats. We believe the sharks follow their preferred prey, squid, on their daily migrations from depths of several hundred metres to the surface and back again.

On the one hand, the results so far have shown that Northeast Atlantic tope - at least the adults that aggregate in the shallow German Bight during the summer months - also undertake long and in some cases apparently specific migrations that take them from their -assumedly regular- habitats in relatively shallow shelf areas, in some cases as far as the oceanic areas of the open Atlantic. On the other hand, it has been shown for the first time in detail that they become “deep-sea sharks” and regularly use the abundant food supply at depths of several hundred meters as a source of energy during their migrations in areas of relative food scarcity in the near-surface water layers.

Further data on habitat use during the different phases of migration and possible regular patterns of horizontal migrations are still being analysed.

The results have already been published in two scientific publications.

Links and Downloads

- See the Thünenpress release for more information : "From the German Bight into the deep sea: The amazing migration of tope"

Interview with Matthias Schaber in Wissenschaft erleben (German version only available): "... a gigantic mass movement - and the tope sharks are joining in"

ICES WGEF: The working group provides stock assessments and recommendations on the status of shark and ray populations throughout the ICES area.

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) / Bonner Convention: Fact sheet tope shark

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Tope (global)

Thünen-Contact

Involved Thünen-Partners

Duration

7.2017 - 12.2025

More Information

Project status:

ongoing

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/media/_processed_/7/1/csm_IMG_7977_large_1defaf5de1.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Logo des Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft](/media/allgemein/logos/BMEL_Logo.svg)